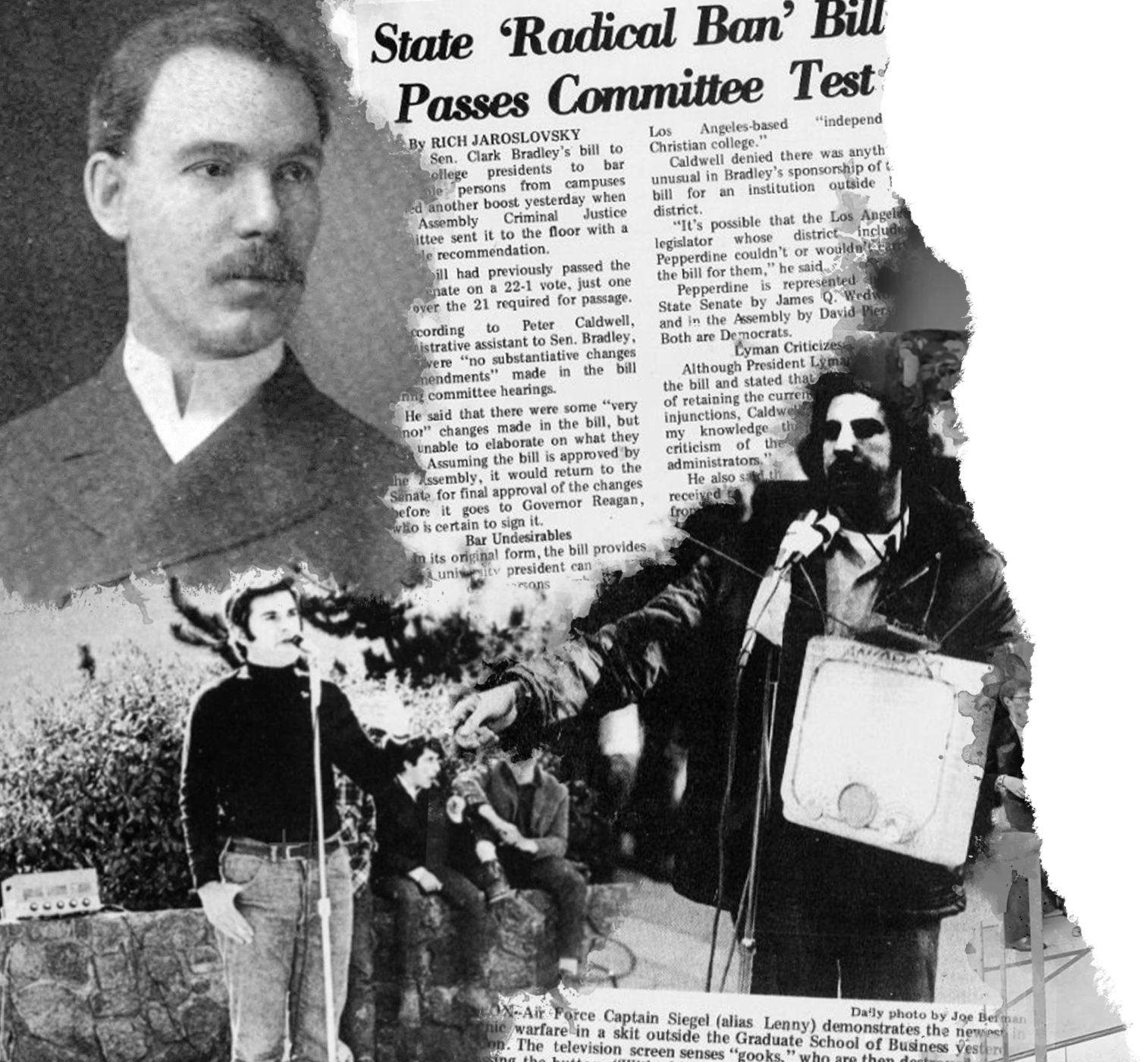

In the height of the Vietnam War, Bruce Franklin was an outspoken professor. Then, he got fired for his activism at Stanford. (Photo: The Stanford Daily Archive)

It’s 1972 at Stanford, and the Vietnam War is raging on. The effects of the conflict can be felt on campus, from student-led anti-war protests to Stanford’s continued involvement in the war effort. Bruce Franklin, a once-tenured English professor, was just fired for allegedly inciting students to “disrupt University functions,” through two public speeches and a verbal protest to police.

Franklin’s firing did not sit well with many students. So, the student body did the thing it was probably most well-known for doing at this time: they demonstrated. Many times. At one rally for Franklin, 300 students tried to seize a building in protest, though they were met by locked doors and Palo Alto police in riot gear.

The events that took place at Stanford were just a snapshot of what was going on across the country. While students at nearly every college protested against the bloodshed and destruction that the Vietnam War caused, parts of the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) were directly involved in supporting the war effort. Stanford’s Computation Center was working on Gamut-H, a government program sponsored by the SRI that was linked to a Navy amphibious attack model.

Many students did protest against the University’s ties to Vietnam, doing everything from shutting down the Applied Electronics Laboratory to blocking traffic to the SRI.

The Vietnam War demonstrated the power administrators, faculty and students all have in setting the tone for their campus on pressing issues. But what steps are all these different stakeholders taking today? And how has the intersection of universities and policies changed in recent years?

Stanford’s historical support for the war and the subsequent dismissal of Franklin starkly contrasts with its current approach to political issues. However, varying viewpoints among faculty regarding the extent and importance of free speech persist, as commonly observed across college campuses.

While professors generally concur that the administration tries to maintain neutrality towards their views, professors seem to still have disagreements between each other regarding personal politics. These disagreements have been exemplified by recent incidents such as controversial comments made by Hoover Institution senior fellow Scott Atlas about COVID-19 and the University’s response to a student demonstration during a talk by federal Judge Kyle Duncan at Stanford Law School (SLS).

Stanford’s historical support for the war and the subsequent dismissal of Franklin differs from the University’s current approach to political issues, which current faculty have described as a more neutral approach. However, there are still disagreements among faculty about the significance and limits of free speech.

David Palumbo-Liu, a comparative literature professor who often speaks out on issues related to progressive politics and social justice, said the administration has been “super neutral” about his personal politics.

Palumbo-Liu was hired to work in the Asian-American studies program after a student protest for ethnic studies. Now, he sees his role at Stanford as someone who is unafraid to challenge authority.

“I’ve never been particularly intimidated by Stanford because that’s what they hired me to do, to be visible and an advocate for studies in race and ethnicity,” he said.

Every one of the faculty interviewed for this story said that they also felt the administration tries to be neutral when it comes to the professors’ political affiliations.

“I think that the University tries to not take stands on things as much as they can avoid it,” Joe Lipsick, a pathology and genetics professor who sets the agenda for faculty senate meetings, said. “I’ve never seen a faculty member discriminated against based on their political views, but there are differences in opinion.”

The changing current events and various responses from University administrators leads to a central question that the country also seems to be grappling with: what is the role of a university in society?

The run-ins with police and seizing of buildings highlight the rising tensions between the administration, professors and students during the Vietnam War. And it had been tense even before Franklin’s dismissal.

On Jan. 14, 1969, a group of 40 students from Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) interrupted a Board of Trustees meeting to urge the trustees to stop any projects relating to Southeast Asia. Of those who participated, 29 students were penalized with probation and fines.

Franklin was known for being outspoken. He was the final speaker at a campus rally to protest the Laos invasion, when he urged the students to “strike” at the Computation Center. His final words were “Shut it down.”

The next day, he was fired.

“[Franklin] was picked out of the [protest] crowd by the moderator from the Hoover Institution even though he was not participating in the heckling,” Lenny Siegel, who wrote a book about the Stanford Vietnam War era, said. “I’m saying that because I was a witness and I testified to that effect.”

The Bruce Franklin Legal Fund wrote in The Daily in 1972 that the Board’s decision to fire Franklin was based on the “uncomfortably heterodox” nature of Franklin’s political views, though the University insisted that it was about his actions, not his beliefs. Of the four charges brought against him, one was thrown out in court in 1978 and one was not sustained.

According to Siegel, Bruce represented a threat to the University that had “relatively little to do with the incidents that he was fired for.”

“There was often a tension between the faculty, which thought it ran the University, and the trustees, and the administration was in between,” Siegel said.

In an interview with the Daily in 2019, when he returned to Stanford to speak about his memoir, Franklin said that Stanford’s involvement in the Vietnam War “changed people’s understanding of the roles of a university in society.”

Palumbo-Liu expressed a similar sentiment about the Vietnam War protests at Stanford, marking them as a special case of protests.

“Bruce pointed out that the University was part of the war effort. People felt that the niceties of the ivory tower had to take a backseat to pressing issues,” he said. “Many of us felt that the U.S. government had broken the law.”

Fast forward nearly 50 years after Franklin’s firing. Campus is rocked by another groundbreaking world event. Except this time, instead of going out into the streets, students are going home to their childhood bedrooms. And instead of carrying around heavy gas masks, students are stocking up on thin surgical masks.

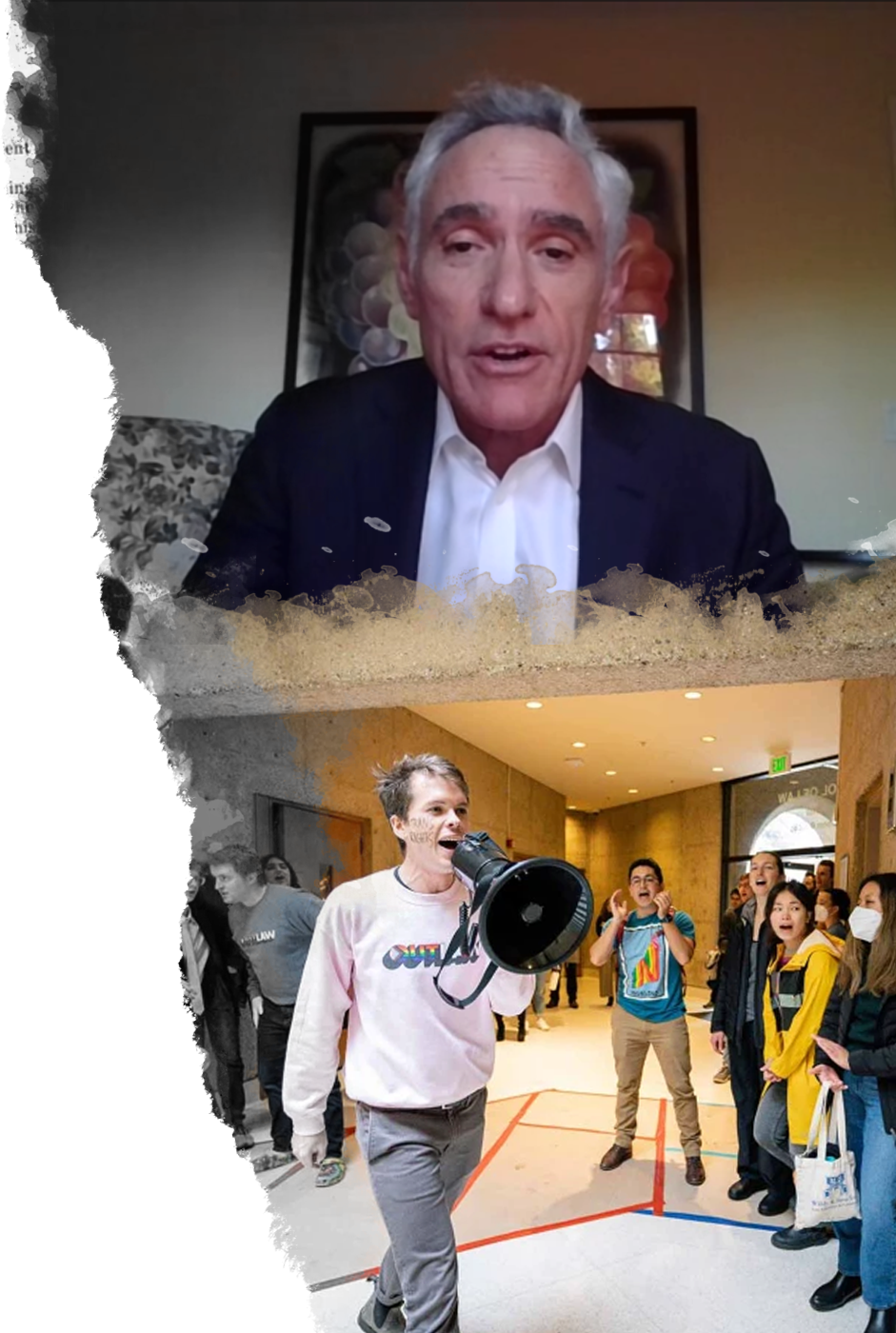

In the thick of the COVID-19 pandemic, former COVID-19 adviser to Donald Trump and Hoover fellow Dr. Scott Atlas was condemned by around 100 Stanford faculty members for his advising on COVID-19 in an open letter organized by former School of Medicine Dean Philip Pizzo. During the pandemic, Atlas suggested that children don’t transmit the virus, questioned the efficacy of face masks and advocated for a “herd immunity” strategy. He also pushed people to “rise up” against Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s COVID-19 public health measures.

After that comment, the University released a statement, saying “Dr. Atlas has expressed views that are inconsistent with the University’s approach in response to the pandemic.” Officials also released a statement saying they supported “using masks, social distancing, and conducting surveillance and diagnostic testing.

Stanford President Marc Tessier-Lavigne, Hoover Institution director Condoleeza Rice and Provost Presis Drell all voiced concern over Atlas’ comments. However, some professors, including Palumbo-Liu, thought that the University did not distance itself enough from Atlas at that point.

The Faculty Senate passed a resolution condemning Atlas for his statements on COVID-19, though they disagreed over whether or not he should be subjected to disciplinary action.

Lipsick said that the Atlas story is complicated.

“I don’t agree at all with what he said and what he did, but he does have a right to say things,” Lipsick said.

He also noted that faculty being responsible for the statement is problematic and raised the question of whether or not faculty should be driving the University’s official stance.

Palumbo-Liu, however, said that he views the issue differently. He said that Atlas “used his connections to Stanford to make pronouncements on things he wasn’t qualified to make pronouncements on.”

“Academic freedom is one value, but it doesn’t trump academic responsibility,” he said.

Atlas did not respond to The Daily’s request for comment.

The University was once again tested a couple months ago on March 9, when Judge Kyle Duncan, who was invited to speak at the Stanford Law School (SLS) by the Federalist Society, was interrupted by booing from audience members who said Duncan supports laws that would harm women, immigrants and LGBTQ+ people. Some people also accused Duncan of playing into the emotions of the protestors by filming them and using inflammatory language, including insulting protestors.

How was the University supposed to respond to this protest? Does freedom of speech outweigh etiquette in academic settings?

In his statement responding to the incident, Tessier-Lavigne said that “the world is a place of disagreement, and we would not be preparing students adequately if we sheltered them from ideas they find difficult.” He expressed Stanford’s commitment to academic freedom and called the events at the law school “deeply disappointing.” Tessier-Levigne also endorsed SLS dean Jennifer Martinez’s “forceful message” and said people are free to “express their views and even protest; what they may not do is disrupt the effective carrying out of the event.”

“I think the administration aspires to be neutral and encourage academic freedom and free speech,” comparative literature professor Russell Berman said, referencing Tessier-Lavigne’s recent statement. “I’m not sure that the ideal situation that he describes in that eloquent statement is an accurate description of empirical conditions at all times at the University.”

Palumbo-Liu, however, felt the reactions from University leadership were excessive.

“The offense was real but not that important in real life,” he said “I think the whole thing was kind of silly.”

The University did not directly respond to the comments from Palumbo-Liu and Berman, but wrote in a statement that the “University leadership respects the wide range of individual viewpoints in our community on issues and events in the world, and therefore most typically issues institutional statements only when there is a direct tie to the mission or operations of the University.”

When reflecting on the role of the University in political matters, Berman pointed to the the University of Chicago’s 1967 Kalven Report as an important set of guidelines. The Report establishes the role of a university in political and social action, emphasizing the importance of institutional neutrality on social and political issues in protecting academic freedom.

“The institution should be like a highway. Anyone should be able to drive on it,” Berman said, referencing the Kalven Report.

Palumbo-Liu said that his feeling on the Kalven Report is that there is no empirical ground zero from which to measure it. That being said, Palumbo-Liu does believe that the University can be a place that holds a multitude of ideas where people can disagree with each other. “I’ve never felt that to be a huge issue because I don’t mind being disagreed with,” he said.

Berman said that he worried, however, that certain University initiatives may draw similarly politically affiliated professorial candidates. Stanford research supports the claim that university faculty are usually liberal: a study by sociologists Neil Gross and Ethan Fosse’s research points to typecasting as a potential explanation. Universities like Stanford have started to prioritize the study of race, class and gender more, as well as promote equity, diversity and inclusion, topics that are typically believed to be more important to liberals, according to Gross and Fosse’s research.

Berman said he’s not prepared to advertise his political leaning, but said many people would regard him as conservative.

“There’s a widespread agreement … that the professoriate in general, is more liberal. I don’t think that’s a controversial claim,” he said.

Palumbo-Liu, however, feels that it’s more nuanced than liberal versus conservative, and that the professoriate falls about middle left. “It means that they are of a kind of liberal persuasion,” Palumbo-Liu said.

But a question still remains: how does the University decide which issues to get involved with, or which issues not to get involved with?

Lipsick said one of the reasons the administration might not want to get involved in certain political matters is so as not to offend donors.

“Stanford is a corporation disguised as a university […] The corporation doesn’t want to get sued and wants to raise money,” he said. “Is there any money that can be too dirty for the university to take?”

The University denied such a claim, stating that “alumni donations have no bearing on institutional statements.”

While the University now seems to remain neutral in political matters, according to faculty, the professors are having debates themselves about what should and shouldn’t be allowed to say.

“We don’t have a problem with it as long as we agree with what’s being said,” Palumbo-Liu said.

As world events shift, the question of what the university’s role in society is remains unanswered, but if one thing is for certain, it’s that the institutional highway is still open, awaiting inevitable traffic and probably some collisions along the way.