This article discusses mental health, depression and suicide and may be triggering to some people.

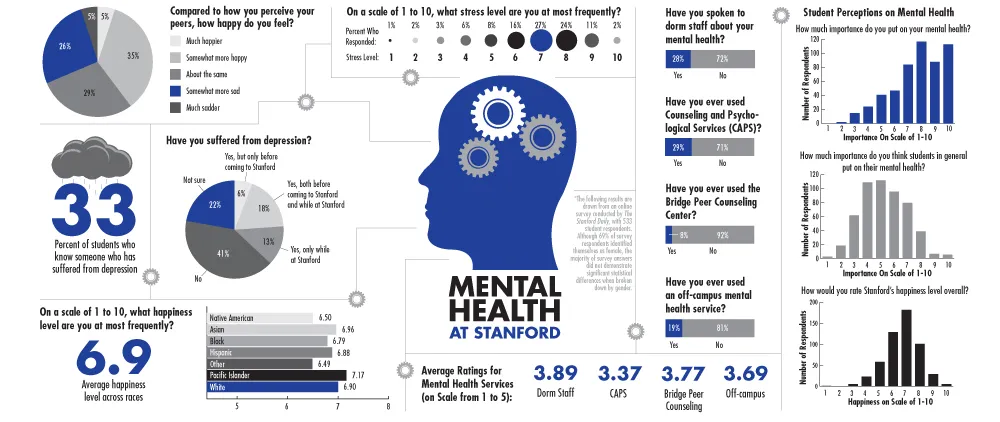

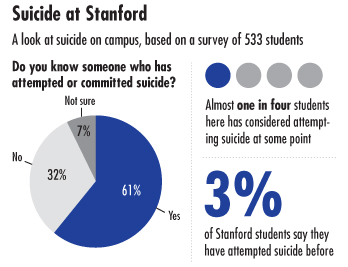

23 percent. That’s how many Stanford students say they have considered attempting suicide. Three percent say they have followed through and actually attempted it.

These are unscientific numbers, for sure. They are drawn from a voluntary, non-exclusive, online survey conducted by The Daily. But over 500 people responded, and so if these numbers are even close to accurate, they paint a picture of the struggles simmering under the surface of life on the Farm.

This is not a “Stanford-has-a-mental-health-problem” article. The reality is that depression and suicide affect everyone, particularly young adults — a recent American College Health Assessment survey found that nationwide, approximately 21 percent of college students have seriously considered suicide, very similar to what The Daily found at Stanford. At the University of Pennsylvania, at least two students have committed suicide since winter break. At Yale, a student recently wrote a harrowing account of her struggles with mental illness.

What this is, is a “Stanford-doesn’t-not-have-a-mental-health-problem” article. Time and time again, online and in-person, students have expressed the outside perspective that because of the physical beauty of Stanford’s campus and accomplished nature of the people on it, Stanford students couldn’t possibly have mental health struggles.

“We at Stanford live in such a paradise-seeming place that we begin to believe that it is indeed a paradise, that Stanford’s (and by extension, students’) baseline should indeed be perfect,” wrote a current junior in response to the survey.

“There’s a culture of ‘we’re the best and everyone is SOOO happy,’ which can be toxic and alienating to someone who doesn’t feel that way,” wrote a current senior.

It should be stated outright: Stanford students do struggle with mental health. They do struggle with depression. They do consider and attempt suicide. And they often don’t know where to turn.

***

Caitlin ’16, whose name has been changed to protect her privacy, was hospitalized twice last year for her struggles with anorexia, bulimia and depression.

The first hospitalization — during the first week of school — was by choice. Needing additional help and not knowing where else to go, Caitlin checked herself into Stanford Hospital, where she stayed for three days.

However, the second hospitalization was not voluntary. After a period of self-harm and a missed meeting with her psychiatrist, Caitlin said that she was taken in a police car from Vaden Health Center to Stanford Hospital’s involuntary psychiatry ward for a five-day stay, something she cited as one of the most traumatic experiences she’d ever lived though.

“I tried to explain, but eventually I was informed that I was going to the involuntary unit,” she said. “I don’t know how to put this without making it seem overly dramatic, but they basically kind of told me that if I was nice, the police wouldn’t handcuff me.”

Caitlin said that her peer health educator (PHE) and the residence dean (RD) were supportive during her initial hospitalization. After she was released from the hospital, the University assigned a team of mental health professionals and University officials to support her. While Caitlin appreciated the support, she said the burden of constant check-ins with her psychologist, psychiatrist, nutritionist and residence dean added additional stress to her recovery process.

“It was good of them, but at the same time it just made me more stressed out because I felt like I had to convince everybody that I was on top of things and meet with like four people every week,” Caitlin said. “Every time they’d be looking at me like ‘Are things okay [Caitlin], are you okay?’ and I just wanted to cry, but I just had to be like ‘I’m happy, I’m happier than I’ve ever been in my life’ and so on because there was so much pressure on me.”

***

One current Stern resident assistant (RA) said he was surprised by the amount of mental health issues within his dorm. He said that during his freshman year, he thought that most of his peers were having a uniformly happy experience.

“Now as an RA, we’re in a position where people do come to us for help and do let us know about their concerns, and so you see all that’s going on under the surface,” the RA said. “There’s a lot. I think it’s a pretty fair statement to say that most freshmen are dealing with some kind of emotional or mental struggle.”

All RAs interviewed were granted anonymity to protect the privacy of their residents.

“Based on my experience, I wouldn’t be shocked if it was at least one person in every freshman dorm that has thought about [suicide],” said another current Stern RA.

Indeed, three of five freshman dorm staff members interviewed by The Daily said a resident had expressed suicidal thoughts to them already this year. They also listed a litany of additional struggles faced by freshmen: eating disorders, homesickness, academic challenges, roommate conflicts, depression and family issues at home.

Mental illness is a big focus of staff training, during which future staffers learn about, discuss and role-play potential scenarios they may face in dorms.

“When they tell you about these things in training, they make it seem like it’s an option — you may deal with some of these things,” said a second Stern RA. “It’s not an option. You will be dealing with everything.”

RAs are also given training in the Question, Persuade, Refer (QPR) suicide prevention techniques. QPR training was introduced at Stanford in 2008 as one of the recommendations of the Student Mental Health and Well-Being Task Force Report.

Alejandro Martinez, senior associate director of Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS), said that QPR was implemented to help the Stanford community better respond to student crises. QPR relies on asking people direct questions about how they are feeling and what they are dealing with at that moment in time, including asking whether they are considering suicide.

“Sometimes we can see someone’s distress, but we have so much respect for people’s privacy, or we think it’s not our business and we don’t want to intrude in someone’s lives, so we hold back,” Martinez explained. “So a program like [QPR] shows us that it’s probably a good idea to sometimes cross that line and be a little more intrusive, but potentially life-saving, to another person.”

“Most of the time when you ask people directly about suicide, they are going to say no,” Martinez continued. “That’s typical — it’s not like every time you ask you’re going to get an affirmative answer. But you have already raised the question and sometimes people will say ‘yes, I have been,’ and that’s the time to pursue additional support for that person.”

Several RAs said that learning when to seek outside help is emphasized heavily in training.

“I think that maybe there are some people who come in and think that by dealing with a mental health issue, you are trying to treat it — that’s not the case,” said a current Wilbur RA. “Even though you as an RA want to completely serve and help your residents, there also comes a point when you are only trained so much.”

For Stanford students, the next step is often the hospital, CAPS or the RD, depending on the severity or immediacy of the case.

***

According to John Giammalva, the residence dean for Wilbur Hall and the Cowell Cluster, it is not uncommon for each of the seven residence deans to have at least one of their students in the psychiatric ward of the hospital.

Giammalva said that the most immediate concern is always the student’s safety. Later, the residence dean will work with CAPS, the student and the student’s family to determine what and where treatment would be most effective. Sometimes, that involves leaving campus, which Giammalva characterized as a difficult decision.

“No student ever wants to leave — I don’t think I’ve ever come across a student that really wanted to take time off,” Giammalva said. “But on the other hand, I think that pretty much almost every single student I’ve worked with, after they’ve taken time off, has come back and said, ‘yeah, I needed that.’”

Caitlin said she understood Stanford’s policy, although she thought that sometimes it was over-enforced.

“It’s well reasoned. You don’t really want someone who is suffering from a mental illness to go to your school because they’re not going to be able to perform at their prime,” she explained. “That’s not good for the school or for the student, so it was good of them.”

Caitlin ultimately decided to take a voluntary leave of absence during spring quarter in order to receive more treatment, and plans to return next fall. Contrary to the reported experiences at other universities, however, she said she is “really grateful” for the support Stanford offered her, particularly now that she is in recovery.

“I feel that Stanford is a very much more compassionate community than many other colleges,” she said. “In my dealings with the whole administration related to mental health and leaving Stanford, to me, it seems as if they cared more about my individual case then they would at say, Harvard and Yale.”

***

Despite the prevalence of mental health issues on campus, students reported difficulty stimulating conversation surrounding the topic. Caitlin said that at the time of her hospitalization, she didn’t know of any other students who were going through the same experience.

Hannah ’14, who has been diagnosed with depression, said that people often don’t understand how mental health can affect students.

“Sometimes, I can’t make myself get up and go to class — that is not me being lazy, that is me having a medical issue, and that sounds dumb to people,” Hannah said. “[People] laugh at how much I procrastinate or ‘oh, you didn’t go to class’ … they know [about my depression], but they don’t make the connection.”

Hannah, who asked to be identified only by her first name, said that even though students are usually aware of mental health issues, they don’t create safe spaces to discuss them and are occasionally insensitive. She shared a recent experience of a classmate attempting to explain the complexities of steel maven Andrew Carnegie by saying that “he was completely crazy, like he should have been on pills or something.”

“As someone who is on medication for mental health issues, the idea of being equated with someone who was a racist, classist, old white man from the 1800s, the idea that that is the perception of people who need help for mental health issues is really troubling to me,” Hannah said.

Many students echoed the idea that the topic of mental health could benefit from increased discussion, either through receiving more emphasis during New Student Orientation and awareness weeks or through regular programming where people could share their experiences and thoughts.

“It’s the kind of thing where you just want to have conversations about it,” one Stern RA said. “I think there’s this stigma and people don’t talk about it. [You hear], ‘oh, someone went to CAPS,’ and all of a sudden you think the person is going through a mental crisis, but in reality, some people just need to go to CAPS to talk. I think that’s a huge thing that we can do at Stanford is break down that stigma.”

The current Wilbur RA said that she thinks the way Stanford students handle stress is unhealthy.

“It’s kind of celebrated and seen as a badge of honor — how stressed you are, how little sleep you’ve had, how much coffee you’ve been drinking, how many units you’re taking,” she said. “Very seldom do you see people say, ‘I’m in 14 units and I slept 10 hours and I’m loving it.’”

“That isn’t celebrated and I think we need to shift that culture a little bit and just recognize that stress is normal in the sense that it will happen, but chronic stress is not something that should be considered normal,” she added.

***

In recent years, Stanford, as well as other universities, has expanded the support it offers students.

“Historically, if you had a psychiatric condition that impacted your ability to be at Stanford, it was kind of too bad for you — people were sad and concerned but that was basically it,” Martinez said. “[Now], there is not only an interest but a legal requirement that we make reasonable accommodations to people, so it’s more possible to be successful at Stanford even if you get challenged by a psychiatric condition.”

Martinez pointed to several initiatives that have been introduced at Stanford in recent years, such as the so-called “Happiness class,” or CAPS’ new StressLess@Stanford program, as well as improvements like hiring more staffers at CAPS and refining RA training.

“Stanford has a very strong commitment to move forward in this direction,” Martinez said. “It has committed significant resources in the last, I would say six years, to make sure that we are in a better position to respond to this increased overall commitment to pay attention to our well-being.”

The Wilbur RA said that it would be helpful if mental health were thought of in a positive, proactive way instead of being treated solely as a disease.

“[You can] ask students to reflect on their own mental health, just like daily check-ins … whether it be through journaling or through meditation or being outside,” she said. “I wish that Stanford did a better job of supporting students and figuring out what are those healthy habits that I want to institute now that can last forever.”

Another Stern RA said that while Stanford has a lot to offer, the beautiful campus, brilliant admittees and award-winning professors shouldn’t be used to gloss over the struggles that students face.

“There is a case to be made for Stanford to highlight that students go through bad stuff, to make other students know it’s okay,” the RA said. “It would be nice if Stanford made more of an effort to highlight the fact that it’s not as pristine as they want it to be seen.”

Contact Jana Persky at jpersky ‘at’ stanford.edu.

If you are struggling with mental-health related issues, please contact Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) at 650-723-3785 or The Bridge Peer Counseling Center at (650) 723-3392.