The University released a draft Tuesday morning of its new Title IX process for adjudicating cases involving sexual harassment and sexual assault. Stanford students, faculty, postdoctoral scholars and staff can comment on the draft via email until 5 p.m. on Sunday, Aug. 9. The new policies will go into effect on Aug. 14, per federal guidelines.

Most notably, federal rules have narrowed the scope of the Title IX Office’s mandate, and require a single adjudication process for students, faculty and staff, where previously Stanford outlined two. The federal rules also mandate that Stanford hold live hearings during which accusers and the accused can be cross-examined.

Changes to the University policy that were not federally mandated include the hiring of external judges to preside over hearings and providing a “process navigator” to all parties. Stanford will now provide only two hours of pro-bono attorney assistance ahead of a hearing, an amount that advocates for survivors of sexual assault find insufficient to support complainants, particularly those with financial barriers.

The draft was scheduled to be released Monday, but Vice Provost for Student Affairs Susie Brubaker-Cole wrote in an email that night that the release and the feedback deadline were both delayed to consider “July 30 feedback from the ASSU.” The ASSU had convened a student advisory board to meet internally with administrators and provide recommendations on how the University should adapt its Title IX policy to comply with federal guidelines. Members of this ASSU advisory board are holding a virtual teach-in at 6 p.m. on Wednesday on the draft policy.

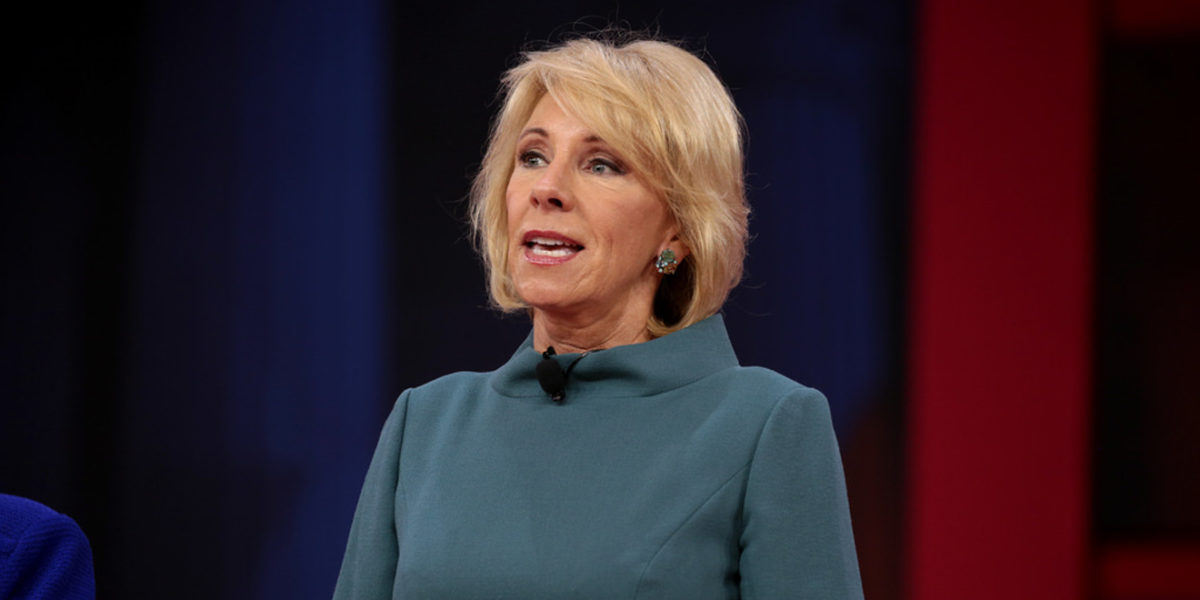

The new policy has undergone substantial changes to comply with the set of regulations released May 6 by Education Secretary Betsy DeVos on how education institutions receiving federal funding must deal with sexual misconduct. DeVos’s final regulations have generated controversy for strengthening the rights of the accused, narrowing the definition of sexual harassment and reducing the legal liability of institutions investigating sexual misconduct claims — which the education departments estimates will result in an estimated 39% fewer investigations per year.

“The new Title IX regulations … include several provisions which we find incompatible with their stated purpose and with the Title IX’s goal to eliminate gender discrimination in access to education,” wrote Maia Brockbank ’21, Krithika Iyer ’21 and Julia Paris ’21 in a public comment. Brockbank, Iyer and Paris serve as ASSU co-directors of sexual violence & relationship abuse prevention.

All three chair the advisory board that provided recommendations to the policy drafting committee, which is led by Debra Zumwalt J.D. ’79, Stanford’s vice president and general counsel. Other members include Persis Drell, the University’s provost; Laura Roberts, psychiatry department chair; Lauren Schoenthaler, senior vice provost for institutional equity and access; Robert Weisberg J.D. ’79, law school professor; Elizabeth Zacharias, human resources vice president; and Stephanie Kalfayan, vice provost for academic affairs.

Consolidating Title IX processes

Per federal regulation, Stanford is now required to have one Title IX process governing all cases; previously the University delineated two separate processes: a Student Title IX Process applicable when the complaint was brought against a student, and an Administrative Title IX Process applicable when complaints were brought against non-student individuals (such as faculty members).

The formal process may begin after the Title IX Coordinator makes an initial assessment as to whether a filed complaint falls under Title IX procedure. At any point after that formal complaint has been filed, parties may engage in a “informal resolution,” or mediation, process. The Title IX Coordinator will, as a part of the investigation process, gather information and evidence regarding the allegations, and the University decides whether to dismiss the complaint or allow the matter to proceed to a hearing (if it was not already settled through an informal resolution). However, the informal resolution is not allowed in cases where the accused is a faculty or staff member, in which case parties must proceed to a hearing.

Preparing for the hearing involves reviewing evidence and drafting written statements, along with preparation for (now-mandated) cross-examination. (Advocates have noted that individuals going through this process would benefit from the help of an attorney, which under the draft policy is available pro-bono only in a limited capacity.)

Following the decision of a judge overseeing the hearing, parties have the right to an appeal. Otherwise, the applied sanction, including expulsion for the most serious offenses, is expected to take place. However, Stanford has expelled few students for sexual assault; since 2000, three students have been expelled, and three “left voluntarily” for reasons related to sexual violence and misconduct allegations, according to a 2018-2019 Title IX report.

The previous Administrative process was “convoluted” and lacked even the clarity that the Student Title IX Process had, according to fourth-year sociology Ph.D. student and ASSU advisory board member Emma Tsurkov. So while folding the Administrative and Student processes into one formalizes the procedure when students bring complaints against faculty or staff, it also means applying a universal new rule in which all parties need to participate in a cross-examination during a hearing. (This did not exist before in the Administrative process, which had no option for a hearing.)

Cross-examination is a deterrent for many survivors of sexual assault in reporting cases, and can be even more discouraging for victims considering coming forward when faced with the power dynamic between student and faculty member.

Process navigators

Under the new policy, Stanford will provide “process navigators” that can advise parties “on all aspects of the procedure.” While the process navigators will be trained in navigating Title IX procedures and University-specific processes “involving sexual harassment, sexual violence, relationship violence and stalking,” and can also assist in efforts such as filing a report to law enforcement, they are not necessarily attorneys, nor can they serve as a complete replacement for them.

For example, conversations with process navigators, which are “intended to” stay confidential, may still be subject to disclosure in legal proceedings, and are not privileged under law like communications with attorneys. Process navigators also cannot speak or advocate on behalf of individuals in the hearing, according to the draft policy.

Legal aid and inequity

In addition to a process navigator, once a formal complaint has been filed, the University will provide up to two hours of consultation with a University-identified attorney to assist in either a mediation process or in preparation for a hearing.

Previously, Stanford offered parties undergoing the Student Title IX Process up to nine hours of pro-bono attorney assistance throughout the entirety of the process. Some attorneys believed even that was not enough.

No party undergoing the Administrative Title IX Process was entitled to attorney assistance paid for by the University, because there was “no hearing and therefore no cross-examination or obligation to make evidentiary objections” in cases against faculty members, according to a previous statement from Drell and Schoenthaler.

Student activists are concerned about how that could disadvantage lower-income complainants, as it allows parties to use attorneys as advocates at any stage of the process (including before a hearing) if they can afford it, but only provides two hours of pro-bono legal aid for those that can’t.

“We explicitly expressed this concern to the administration but it was largely disregarded,” Brockbank wrote in a statement to The Daily. “This new policy is knowingly setting up a system of inequity counterintuitive to Title IX in which wealthier students will be given higher quality, unlimited legal advising, and therefore an extraordinary advantage in the Title IX proceeding.”

Under new regulations, more extensive legal aid is only available if the matter proceeds to a hearing — at that point, Stanford will provide an attorney to assist the parties in preparing for the hearing, conducting cross-examination during the hearing, and assisting during an appeal period. However, the draft policy is unclear about just how much assistance that attorney will be able to provide (and whether that assistance will exceed the previous guarantee of nine hours), only stating that the University will pay a “flat fee” to the attorneys for their services.

Ultimately, Brockbank said, legal aid provided at the hearing stage is “somewhat moot” because it will likely affect very few cases. In the 2018-2019 year, only five hearings took place out of over 300 total cases reported or resolved in that academic year.

Brockbank notes that even then, attorneys available pro-bono to parties are drawn from a pool selected by Stanford. The draft policy notes that the University-identified attorneys on its lists “owe a duty of loyalty to their Party clients, not to the University.” (Stanford drew scrutiny in 2017 for dropping one of its Title IX lawyers, Crystal Riggins, after The New York Times quoted her criticizing Stanford’s Title IX procedure. Schoenthaler wrote then that Riggins’ criticisms displayed a “disappointing” lack of faith in the process, and that it “does not make sense for the University to continue to refer our students to [her].”)

Advocates point out that while the federal rules are strict in some areas like mandating cross-examination, there is nothing in those regulations that prevents Stanford from offering more legal aid to parties before the hearing stage in order to make the process more equitable.

Mandated cross-examination

New federal guidelines mandate that Stanford hold live hearings (which may be held virtually) during which both accusers and the accused may be subject to cross-examination. Stanford’s draft policy allows both parties to jointly waive this process, and opt for submitting written cross-examination questions to the hearing officer.

Advocates for survivors of sexual violence have maintained that the cross-examination procedure creates a hostile hearing environment for victims, and is often “unnecessarily retraumatizing.” That alone may decrease reporting rates — potentially by 50%, according to estimates by the Association of Title IX Administrators.

It may also result in more cases being handled in an “informal resolution” process, which can be agreed upon by the complainant, respondent and Title IX Coordinator at any point after the filing of a formal complaint. There is no limitation on the seriousness of the complaint that can be resolved through this mediation process; Brockbank, Iyer and Paris note in their public comment that victims of sexual violence may feel “coerced to enter a mediation process in which they would have to face their assailant and will be pressured to compromise.”

If parties choose to undergo a mediation before the hearing stage, only two hours of pro-bono legal aid will be provided, which Brockbank describes as insufficient. Those who can afford an attorney to assist in the mediation will have an advantage over those who can’t — and must rely only on two hours of legal aid and a process advisor — in navigating what is still a complicated and legally strategic procedure, which some lawyers have likened to plea bargaining.

Judges to preside over hearings in place of in-house panel

While not mandated specifically by federal guidelines, the University will be hiring non-Stanford “neutral decision-makers” with professional legal experience, such as retired judges, to preside over hearings (and appeals) and consider allegations, apply evidentiary standards and make determinations of responsibility.

The draft policy only specifies that the judge serving as the hearing officer must not have a conflict of interest (which can be challenged by either party) or a “current affiliation with Stanford.” Members of the ASSU advisory board have requested that the policy explicitly exclude Stanford alumni, donors and parents from serving as hearing officers or as appeal officers.

Previously, a three-person panel of “trained members of the University’s community” presided over the hearing and would come to a unanimous 3-0 verdict in determining a sanction of expulsion, suspension or probation. Stanford adopted this particular setup following national criticism over its previous system, which required a five-person in-house disciplinary board (drawn from a pool of administrators, faculty and students) to meet “an uncommonly high bar” of 4-1 to find an accused student responsible for sexual assault. In two hearings on the same case, a majority — three of the five panelists — determined that a Stanford football player had committed sexual assault, which was not enough.

Narrowing Title IX jurisdiction

DeVos’s proposed rules noticeably narrow the jurisdictional and definitional scope of Title IX, though advocates have noted that the University could use other University policies like the Code of Conduct or Fundamental Standard to address conduct outside of the narrower scope.

As far as jurisdiction goes, the Title IX Office is now limited to investigating instances that take place on campus, or off-campus in school-sanctioned housing or at events where the school exercises “substantial control” or students and activities (like field trips or conferences). This, and Stanford’s draft Title IX policy, explicitly exclude reported conduct that occurs at study-abroad programs or other off-campus locations.

The policy may limit Stanford’s responsibility in addressing online sexual harassment and cyberviolence, particularly if it occurs “off campus” from home computers or cell phones. The draft policy does not make explicit how the University will move forward with investigations into Title IX complaints brought during a period of time where the vast majority of interaction between Stanford students and faculty are occurring online. However, the Title IX Office’s website says that “harassment or discrimination that occurs within a program or activity of the University, including all online instruction” will be subject to University policy, and that they will respond to concerns outside of that scope if the conduct is “so severe as to cause significant harm within the University community.”

Narrowing the definition of sexual harassment

The education department has also changed the definition of sexual harassment from an “unwelcome conduct of sexual nature” that “creates a hostile environment,” to the Supreme Court’s definition as “unwelcome conduct that is so severe, pervasive and objectively offensive.”

The federal guidelines use a stricter definition than the University does in its Administrative Guide 1.7.1, which addresses sexual harassment. Stanford’s new Title IX policy notes that conduct that falls outside of the scope of Title IX but violates 1.7.1 “may be addressed through other University processes.”

In the draft policy’s press release, Provost Persis Drell wrote that the University is “committed to ensuring an appropriate response to all allegations of sexual harassment and assault that occur within a Stanford program or activity, including acts that do not fall within Title IX’s scope.”

The Daily has reached out to the University for comment on if they plan to put forth a more explicit policy that governs cases that fall outside the scope of Title IX.

Evidentiary standard

Federal rules offer colleges a choice between using two standards for burden of proof in hearings: the “preponderance of evidence” standard and the “clear and convincing evidence” standard, the former of which is less rigorous and means that the alleged action “more likely than not” occurred.

The University will continue to use the “preponderance of evidence” standard, per California Education Code 67386.

Opportunities for institutional choice

Prior to the release of the new Title IX update, students and faculty had expressed concern over how the federal rules might impact the Stanford’s Title IX process, particularly at a university that has seen persistent sexual violence, particularly affecting undergraduate women and transgender, gender queer or nonconforming (TGQN) students.

A campus-wide sexual violence survey, whose results were released initially in October 2019, showed low confidence in University resources addressing sexual violence, including the Title IX Office. Only 23% of victims of sexual harassment or assault attempted to reach out to the Title IX Office, and only 44% of surveyed students believed that campus officials, if notified, would be likely to conduct a “fair” investigation. For undergraduate women and TGQN students, that level of confidence is even lower.

Advocates maintain that raising that confidence will require efforts by the University to exploit flexibility that the federal guidelines allow for in implementing Title IX policy to increase the likelihood that sexual misconduct is reported, and as members of the campus community have suggested, adjudicated more fairly.

In the press release, Drell asked community commenters to keep in mind that there are some parts of the policy “that many thoughtful individuals within the Stanford community will not agree with [but] are set by law and cannot be altered.”

However, while federal Title IX regulations provide for measures that Stanford must adopt and measures that they are permitted to adopt, there are also actions that the University can take that aren’t directly addressed in federal rules. This area is where universities have flexibility.

Christine Helwick ’68, who has filled in for attorneys on leave in Title IX investigations at Stanford and also served as general counsel for the California State University system, wrote in a statement to The Daily that “generally speaking, colleges have a lot of flexibility to develop a process that is more exacting than what the Title IX regulations require.”

Title IX regulations are a “floor” that sets the minimum requirements, she added.

“Title IX reform is only the beginning of the conversation,” wrote Jonathan Lipman ’21, also a member of the ASSU advisory board, in a statement to The Daily. “We can’t lose sight of the need for more effective prevention measures and a thoughtfully crafted process to deal with conduct that will soon fall outside the jurisdiction of Title IX under these new regulations.”

This article has been updated to include information about evidentiary standards.

Contact Elena Shao at eshao98 ‘at’ stanford.edu.